Illustrations for Dante’s Inferno. Drawings by Rico Lebrun. Worcester: Worcester Art Museum, 1962.

Call number: NC 1075 .L35 R4V1962 (Main Library)

Countertop: “Illustrations of the Divine Comedy”

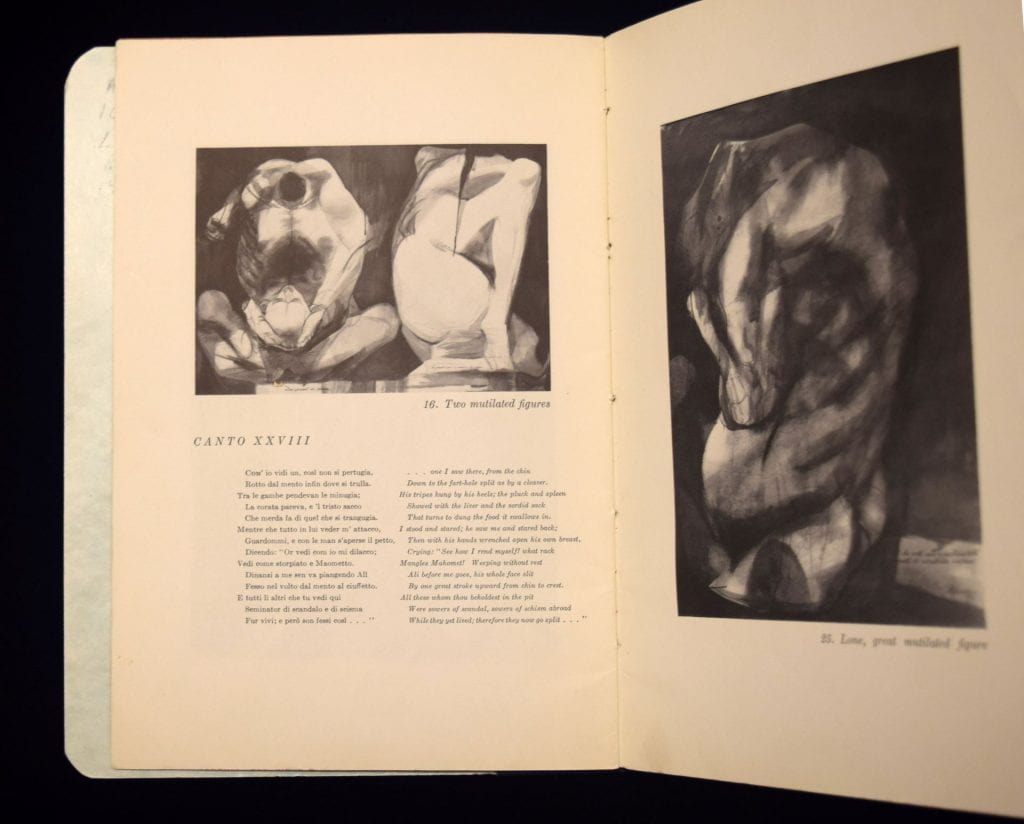

This small edition features a selection of the eleven illustrations that Rico Lebrun (1900-64) made for Dante’s Inferno late in his life. Lebrun’s illustrations emphasize the disfigurement and mutilation of the infernal souls and the tension toward a resurrected humanity. As the artist comments in the introduction to the book: “I find that I bring even to the most splendid images of Dante a resisting irony towards the appalling concept of divine vengeance and infinite pity for the Judge” (p. 3). Lebrun’s use of white and black creates a dramatic atmosphere that the contortion of the bodies even increases.

Students’ Assignment: Abby, Lexi, Isidoro

For this assignment, we compared a selection of illustrations from Botticelli’s drawings for Dante’s Inferno, Roe’s Blake’s Illustrations to the Divine Comedy, Clark’s The drawings by Sandro Botticelli for Dante’s Divine comedy, Brieger-Meiss-Singleton’s Illuminated manuscripts of the Divine comedy, and Illustrations for Dante’s Inferno. Drawings by Rico Lebrun.

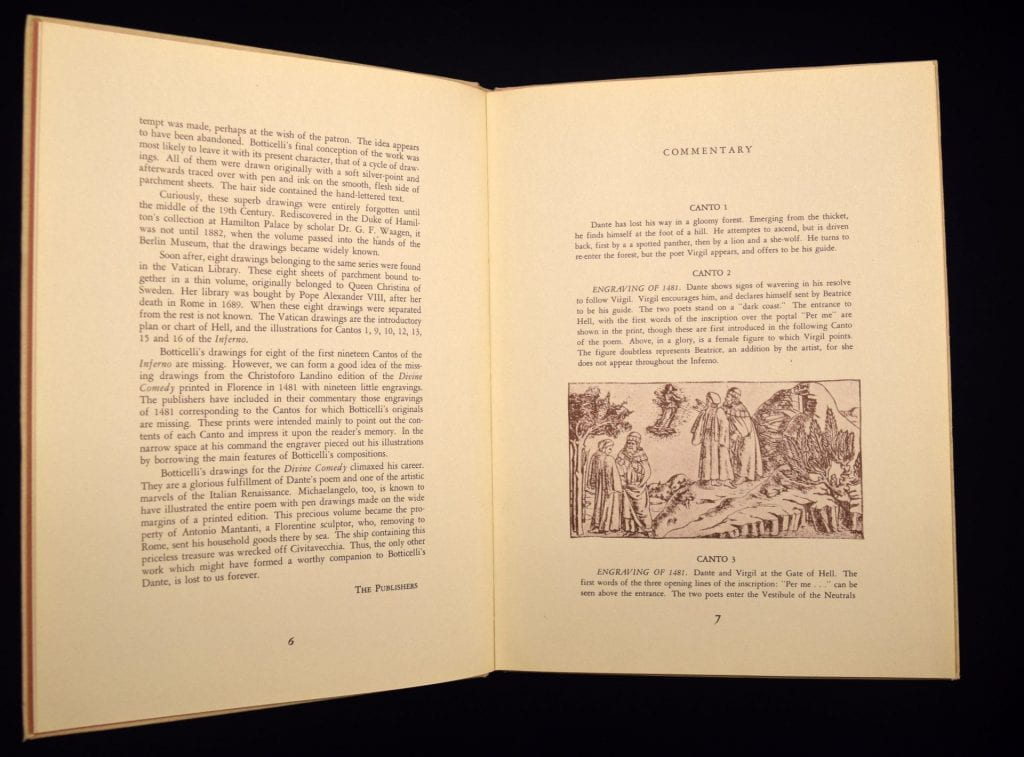

Botticelli’s drawings for Dante’s Inferno, p. 7 (cantos 1, 2, and 3)

The key events in Inferno‘s Cantos 1-3 are illustrated as three simultaneous scenes in the above illustration. The first scene, on the far left, shows Virgil and Dante meeting outside of the dark wood for the first time. Dante has been stopped from his upward climb by the three beasts when he encounters Virgil, who agrees to guide him through Hell and Purgatory, leading him to the entrance of Paradise. The first scene captures the sentiments of Virgil as a guide and Dante as a follower, with Virgil standing taller than Dante, meaning he has authority over Dante. They greet each other with their palms up, a sign of peace.

The middle scene depicts an event from Canto 2. In this canto, Virgil tells Dante how Beatrice sent him to guide Dante through the underworld. In the illustration, Beatrice is suspended in the sky, motioning to Virgil. This highlights the divine qualities of her character, showing that she is a being from Heaven. Virgil and Dante both stretch out their hands toward her, signifying their reverence for such a holy being. The presence of Beatrice conveys hope in a time when Dante is feeling despairing.

The third scene on the far right shows the gates of Hell. One can make out the words “Per me,” which are the first words (in Italian) of the inscription over the gate of Hell that Dante recounts in Canto 3. The last line of this canto (line 142) states, “I entered on the steep and savage path.” This steep path is illustrated in the picture as a rocky walkway leading up to the gate of Hell.

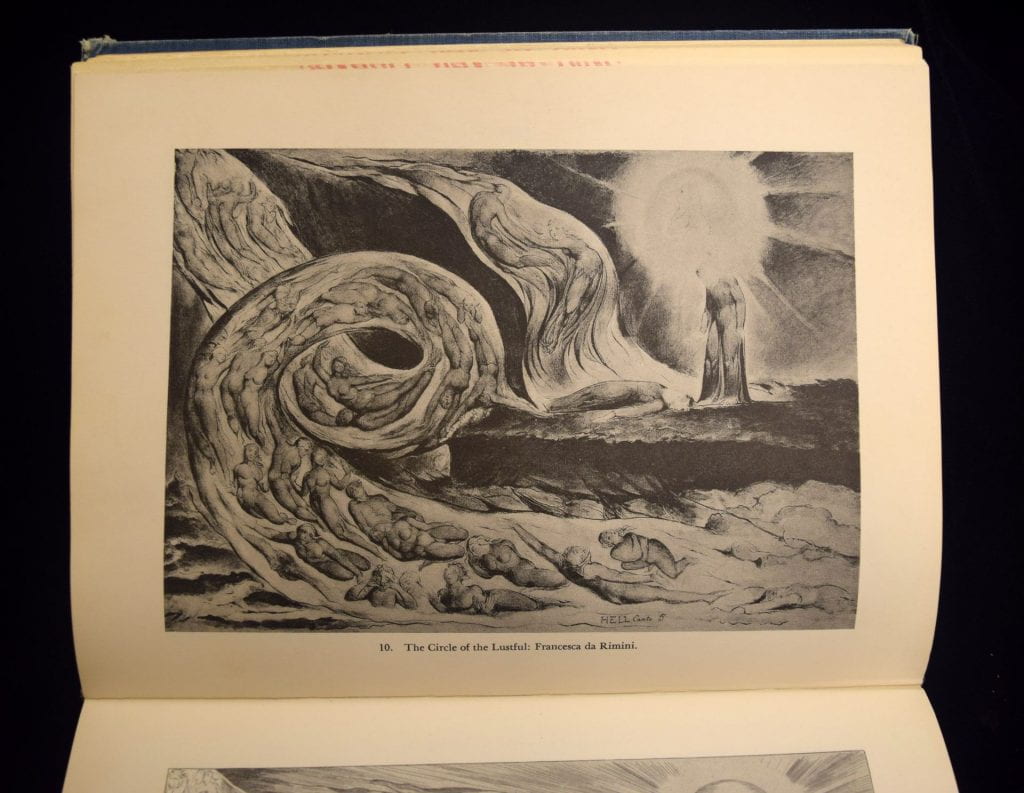

Albert S. Roe, Blake’s Illustrations to the Divine Comedy, f. 10E (canto 5)

The image above shows the Circle of the Lustful in Canto 5 of Inferno with Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta. This depiction shows Dante calling over the two lovers, whose souls are condemned to hell after committing lustful sin in their human lives. The souls are described as being blown about by a terrible hurricane. In the picture, they are trapped in swirls of wind, forced to obey its whims, wherever they may lead. This famous representation of Francesca and Paolo similarly uses a mixture of expressive, bold, and black lines to bring the eye sweeping across the page to follow the souls being eternally whipped around by violent winds. The exaggerated curvature of the figures seem to pull and stretch, bend and contort the forms. Blake’s work is a strange yet striking representation, combining movement so electric that the viewers almost feel as if they will be swept away like Francesca and Paolo. The pity stricken Dante seems defeated and disturbed, while the souls of Francesca and Paolo appear to fade into one another.

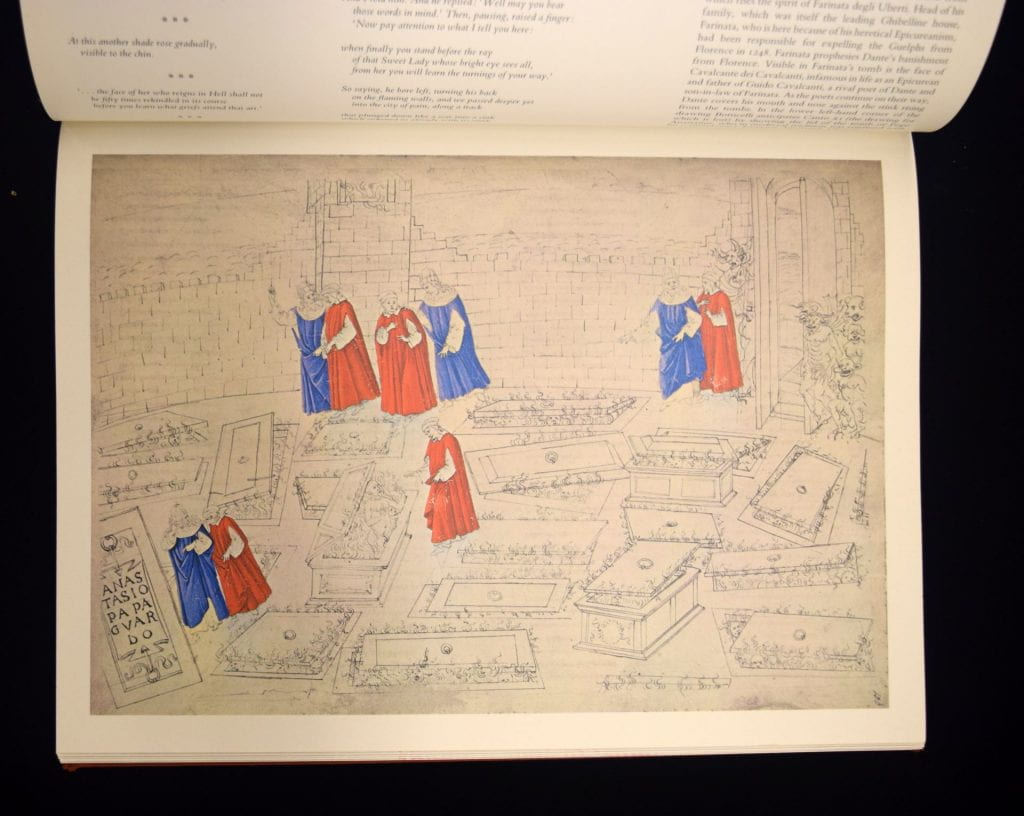

Kenneth Clark, The drawings by Sandro Botticelli for Dante’s Divine comedy, Inferno 10

This illustration represents events in Canto 10 of Inferno. Dante and Virgil make their way through a graveyard of sorts, filled with uncovered sepulchers. Farinata’s voice calls out to Dante from one of the open coffins. During his conversation with Farinata, Dante also meets Cavalcante, the father of one of Dante’s contemporaries and friends, Guido. In comparison to the other Botticelli (Botticelli’s drawings for Dante’s Inferno, p. 7), we see the two figures – Dante in blue, and Virgil in red – emerge from the right most side of the page and lead the viewer leftward. Graves can be seen littering the ground, overgrown and decrepit. Demons are piling over one another watching as Dante and Virgil must find a new entrance into this ring of Hell. There are no trees nor expansive landscapes in this Botticelli drawing, nor is there the graceful presence of Beatrice to comfort Virgil.

The figures move across the page in succession with the canto. Dante can be seen alone speaking to Cavalcante, the lid of his tomb cracked open. The vibrant and saturated cloaks that cover the two men not only are the first thing the eye goes to on the page, but is also representative of their presence in Hell. Dante is just as noticeably human as he is noticeably cloaked in red. Botticelli’s wispy and fine lines suggest a smoky, eerie atmosphere that the two protagonists must navigate through.

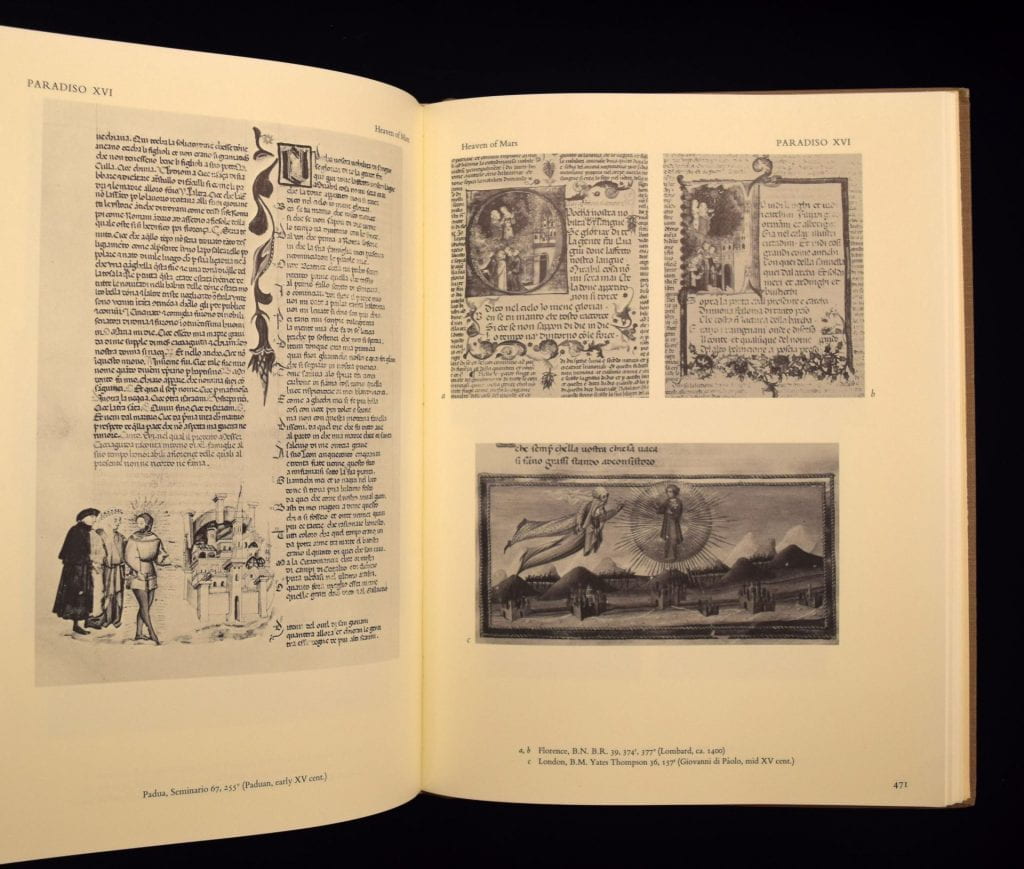

Peter Brieger, Millard Meiss, Charles Singleton, Illuminated manuscripts of the Divine comedy, and Illustrations for Dante’s Inferno, Vol 2: pg. 471, figure c

Imagine now Dante’s ascendance through Paradiso. The illustration at the bottom of the page above depicts the events of Cantos 15 through the beginning of 18 in Paradise. Beatrice and Dante enter the heaven of Mars at the end of Canto 14 and transition to the heaven of Jupiter in Canto 18. In Cantos 15-17, Dante meets his great-great grandfather, Cacciaguida, who had died in the Crusades, making him a martyr worthy of the heaven of Mars. Dante is seen being swept by Beatrice to meet Cacciaguida, who is surrounded by rays of light and wears the cross of a martyr, both signifying that he is a righteous and holy man. He motions with his hands to show that he is speaking, specifically he is recounting his life and the lives of Dante’s ancestors. He also gives Dante a glimpse into his future, revealing that he will soon be exiled from Florence. The story of his heroic and respectable ancestor pleases Dante, who has his hands clasped together as he listens to him.

Beatrice, as Dante’s guide, has her arm around Dante. Her light hair and dress both flow in the wind behind her, giving her an angelic and divine air. No longer is Dante trudging through the chasm of Hell, but rather he is being lifted from the ground by the majestic Beatrice. All of these elements, along with the organized, clean structure of the buildings that line the bottom of the image, contribute to the sanctitude of Paradiso.

Illustrations for Dante’s Inferno. Drawings by Rico Lebrun, f. 16 (canto 28)

This image, titled “Mutilated Figures” is a rather contemporary representation of Inferno, Canto 28. This canto grotesquely depicts the sinners in the ninth circle of Hell, which is the place where the Sowers of Discord and Scandal as well as the Creators of Schism within the papacy are condemned. Here, the damned souls are to walk around the chasm until they arrive at the devil himself, who then slashes them with a longsword in accordance to the nature of their sin. The expressive brush strokes depicted in the images mimic the slashes of the longsword. Sickly contrasting blacks and whites bring to light the pale, parchment thin bodies of the souls doomed to eternal blackness: the once fleshy human bodies are now sorrowful shells. The leftmost figure, Bertran De Born, gently clutches his own head, shoulders slumped in despair and weariness. Ink blots drip from the top of the page, which evoke notions of blood, or perhaps tears. “Mutilated Figures” brings to light just how gruesome the pits of hell become, showcasing also the difference between the start of Dante’s journey of Hell and its end.