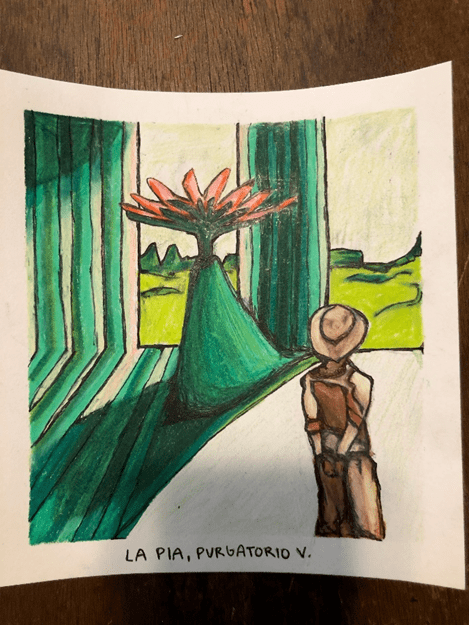

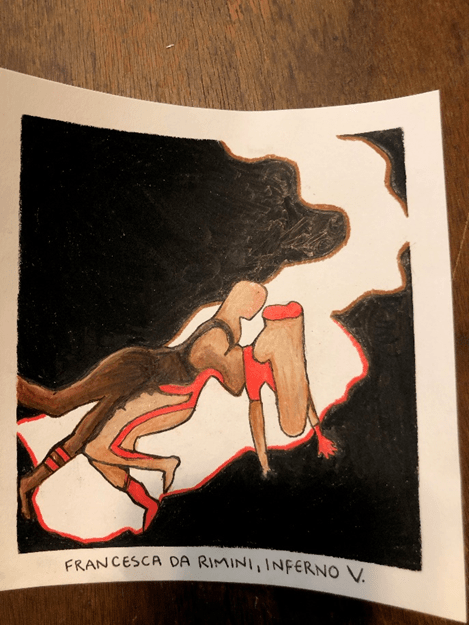

Ava Buchanan: “Francesca and Pia in Watercolors“

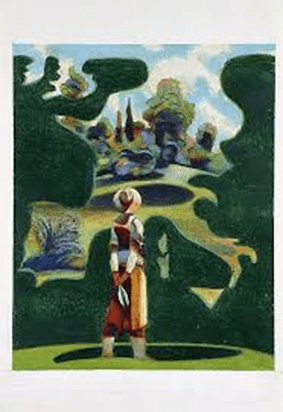

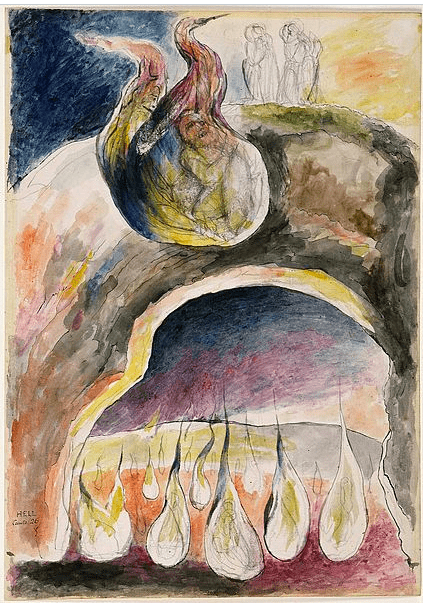

For my final project, I decided to focus on two important and famous female characters within Dante’s Comedy, and aimed to implement Lorenzo Mattotti’s, a modern Italian artist, unique artistic style to represent Pia and Francesca da Rimini. Specifically, I imitated Mattotti’s use of color and geometric shapes to convey emotions. For my “La Pia, Purgatorio V,” illustration, I took inspiration from two of Mattotti’s original works. For the character of Pia, I used an untitled work by Mattotti (Figure 1) to gain inspiration and reference for her stance and body proportions. The body language of this woman seems wistful and confident, and I felt that this was a good representation of the silent determination that Pia is remembered for in the Divine Comedy. For the surrounding background, I referred to a painting called “Rituali Intimi” (Figure 2). Because I am not an artist, I combined elements from these illustrations to create an image that I believed represented the atmosphere and emotions of Pia within Canto V of Purgatorio. My “Francesca Da Rimini, Inferno V” illustration features the characters of Francesca and Paolo as they are carried through the winds of Hell. For the figures of Francesca and Paolo, I conveyed a more abstract and less complex body style than that of Pia. For reference, I used an untitled Mattotti illustration (Figure 3) because I thought that the way the two figures were attached and seemed to blend together was close to the way Francesca and Paolo are represented in Canto V of Inferno. Francesca, who is often remembered as one of the most famous and tragic women in the poem, is represented in my illustration by light browns and red colors. Paolo, her infamous lover, is mainly rendered by darker colors and only two lines of red. Wrapped up in an affair, the red represents the passionate feeling and conflict that I imagine her character to feel. The lighter colors were intended to represent her perceived closeness to holiness and love. Paolo, on the other hand, is mainly illustrated in darker colors which intend to convey his passive attitude and lack of passion in comparison to Francesca’s. Such colors also evoke Paolo’s closeness to the dark background vis-à-vis Francesca’s lighter colored body that stands out among the other souls in Inferno.

Cesca Craig: “Dante in the Dark Wood”

Lines 1–6 from the first canto of Inferno set the primary scene for the mosaic I created, entitled Dante in the Dark Wood. It depicts Dante, in his signature red cloak and laurel wreath, standing alone in the “dark wood;” above Dante, separated by a light green border, is Paradise, which is comprised of mostly white tiles with mirrored tiles also scattered throughout (Inferno, Canto 1, line 2). It seems that artists favor representation of the following lines of this initial canto, in which Dante meets the three beasts and then Virgil, over the initial setting of Dante alone (Inferno, Canto 1, lines 31–81). However, I found a representation of Dante alone to be more compelling due to the symbolic opportunities this initial scene presents. In the center of Paradise is Beatrice, shown as a blonde-haired figure clothed in red, white, and green with light emanating from her; the colors of her clothes are representative of Dante’s description of her appearance—specifically, as he states, “her white veil girt with olive, a lady appeared to / me, clothed, beneath a green mantle, in the color / of living flame”—when he first actually encounters her in the Comedy, in the earthly paradise atop the mountain of Purgatory (Purgatorio, Canto 30, lines 31–33). This scene from Paradise in the upper part of this mosaic is not representative of one particular scene from Paradiso, rather, it is an amalgamation of scenes from Canto 2 of Inferno, Canto 30 of Purgatorio, and Canto 3 of Paradiso; in the first two cantos, aspects of Beatrice’s physical appearance and motivations are detailed and in the third, visual aspects of Paradise are described. Mosaic, as a durable and lasting medium, encapsulates the timeless and everlasting nature of Dante’s Comedy. Further, the medium of mosaic is often associated with images of a religious nature, a category in which Dante’s Comedy certainly fits, as Dante is ultimately a man of God. Additionally, there are explicit mentions of glass and mirrors throughout the Comedy, such as the descriptions of “polished glass” and “mirrored images” as similes for certain aspects of Paradise (Paradiso, Canto 3, lines 10, 20).

Cameron Gunter: “Dante’s Empyrean“

In my own visual representation of Dante’s Paradiso, Canto 30, I chose to use the form of collage to illustrate the contents of the Empyrean Heaven— the highest heavenly sphere. The Empyrean contains those who believed in the Christian God before the figure of Christ and those who believed after Christ, the children born after Christ and the children born before Christ, and, in the center, the Sea of Light. The light which encompasses heaven leaves Dante struggling to see on his journey, but as he reaches Empyrean he describes being encompassed by “a living light” which feels to him like a “sudden flash of lightning, that scatters the spirits of sight” (lines 46-51). Collage seemed to be the best option to explore these elements, first because it mirrors the medium of mosaic, an art form often used during Dante’s lifetime to depict the histories and stories in his culture; second because it gave me the opportunity to experiment with colors to express the light characterizing the heavenly spheres of the Empyrean. Gustave Doré’s wood engraving, The Divine Comedy’s Empyrean, served as a model for my artwork thanks to its spherical descriptions of Dante’s heaven. I based my collage on this illustration, intending to have my own adaptation mirror the depth and boldness Dante describes in a way which those who are familiar with Dante’s Paradise and Empyrean would recognize. I wanted to stay as true to Dante’s description of color as possible in my own adaptation. Lines 61-66 and 109-14 served as my basis for what colors I would use. In reference to the “two banks,” the “hillside,” and “opulent greenery,” I selected to incorporate shades of green in the furthest circle from the Sea of Light with bits of blue scattered about representing the water of the river. For the middle circle, I found myself inspired by the “wondrous spring blossoming,” and the mention of the “flowers” and “rubies,” which led me to select reds and pinks to represent Dante’s vibrant imagery. In the circle closest to the Sea of Light I used yellows, oranges, and whites to capture the “gold” that Dante describes throughout canto 30, the purity of Empyrean as the highest sphere of heaven, and the way in which the third circle described in canto 33 seems to breathe fire (Canto 33, line 120).

Pablo Linares de Avila: “Multidimensional Dante“

For my final project, I decided to work on video games. Although there are already some video games in the market like “Dante’s Inferno” by Visceral, I decided to come up with a completely different idea of video game that allows gamers to make their own decisions at the time of playing. Probably, Dante’s most important lesson is that people need to make decisions in their lives and avoid to be neutral, otherwise they are confined in the external part of hell as outsiders. This specific aspect has motivated me to think of a video game that is consistent with Dante’s negative perspective on neutrality vis-à-vis positive attitude towards decision-taking characters. I decided to name my video game, “Multidimensional Dante”, because of the various decisions that can be made throughout the game. First, the players will have the freedom to customize their main character however they want, not just externally, but also personality wise. I would like to point out that these two ideas are not new at all, since they have already been used in other video games, including ”Infamous” and “Dark Souls.” Additionally, in my video game the players will be able to choose completing their journey in hell, purgatory, or paradise. These three places will be loaded with unique adventures, memorable NPC (non player characters), and much more. Thanks to these features, everybody will have a much more enjoyable, accurate, and informative experience than the one that past video games offer in a more restrictive way. It is worth pointing out that my final project took on a general approach. It did not focus on specific cantos of the Comedy as it emphasizes the uniqueness of the three canticles and pretends to give more importance to characters and events featuring in Purgatorio and Paradiso.

Steve Meehan: “Hanging with Lucifer in Hell for Eternity“

Like Dante, for my final project I decided to be the sole judge and jury of those currently living figures who will spend eternity in Giudecca along with Lucifer. I offer my judgement on these individuals based on the lasting negative impact that I believe they will exert globally over the next few generations and beyond. I chose them in reference to Circle IX of hell, which is reserved for sinners of treacherous fraud, traitors, as well as betrayers (Inferno, Canto 34). In this century and the previous one, a global battle is being waged over the fate of democracy. Governments based on individual rights, civil liberties, free enterprise, and consent of the governed are being attacked and usurped globally. Pope Francis has repeatedly called out this attack on democracy after various events threatening it (January-September 2021). Additionally, the White House held a Global Summit on Democracy attended by over 100 countries (December 9-10, 2021). The listed leaders have turned from democracy to authoritarianism. They are attacking immigrants and gay rights. They have changed their economies over to cronies getting rich off of their people. They have rigged elections, stifled the press, and jailed dissenters and opposition leaders. They use the power of the state to keep control and to impose their will.

Lexi Meredith: “Piccarda Donati in Fabrics“

For my visual representation, I explored textile/fiber arts as a medium to translate Paradiso, Canto 3 by using Piccarda as the vehicle to tell the story of those souls who were forcibly removed from their vows. I played with white fabrics because they would clearly illustrate the heavenly ambiance of Paradiso. Being that Piccarda was sent to paradise, I wanted to reflect the heavenly atmosphere of the Sphere of the Moon with various white fabrics. I specifically chose quilting fabrics with small, floral details printed onto the surface to help add visual texture and interest. At the bottom, to establish the foreground, I created pillowing overlapping forms to represent clouds. All of these helped to ground the rest of the piece and create a stable and central place to look. Rising from behind the clouds is a pastel-colored sun. This is to symbolize that, despite being in Paradiso, the souls are not quite at the height of God’s light, which can be experienced at its full energy only in the Empyrean. Scattered around the top third of the piece are small shiny beads on which I individually hand sewed. The beads range from clear to pearlescent to almost iridescent. Smaller, darker gold beads are also sewn on, fluctuating between the other white beads. I specifically chose these beads to represent the other blessed souls that have been placed in this Sphere and that are floating far away from the central foreground. To the left of the piece, two abstracted figures appear: one out of geometric designed red fabric and the other out of vertically striped blue. These represent the pilgrim Dante and his guide Virgil. I purposely placed Virgil’s representation (the blue figure) in front of Dante (the red figure) to show that Dante is stepping forward and outward. By this point in the Comedy, indeed, Dante’s confidence has grown tremendously and is ready to be make his own decisions. I took some liberty of my own by adding to my scene Virgil, who is not a blessed soul and cannot access paradise with Dante. I feel disappointed by this ending and felt that everything Virgil has done to guide Dante so far leaves him deserving of a better ending. To the right of the piece, we see a bright yellow figure which represents Piccarda. I chose yellow because of the blessed and heavenly light that surrounds her and makes her almost indistinguishable. Surrounding the top of her head are rays of light (smaller cut bugle beads gold in color), almost like a crown, that distinguish her from Dante and Virgil.

Tucker Onishi: “Ugolino’s Pit“

For my final project, I created the cover art of a made-up video game, which I chose to call “Ugolino’s Pit.” The few video games that exist and are based on Dante and his work are not exactly very well received in the gaming market. Many of these games are not just limited by their technology, but arguably by the developer’s lack of vision and drive to create something truly unique and innovative. Thus, my project’s objective is to redeem Dante’s Comedy and make his work part of the gaming community where it justly belongs. The plot of my video game is based on the story of Count Ugolino and his family members and its goal is to make the player empathize with Ugolino’s feelings. In my design, I included an image of a stone dungeon for the background, a picture of a refugee child, the ESRB rated M icon (indicating that the game is for mature audiences due to its gruesomeness and harshness), and Jean-Baptist Carpeaux’s sculpture of Ugolino. The design is topped with a heading that reads: “Chiesta Studios Presents: Ugolino’s Pit.” The game takes place in the prison in which Ugolino, his sons, and his nephews were imprisoned and left to starve to death. The objective that the player needs achieving is simple: Do not starve to death and do not let your family starve to death. Since Ugolino was not fed during his imprisonment, then neither will the player, but food and resources will occasionally fall through a large round grate much like that food that the citizens of Pisa dropped. The difficulty setting affects the food demands of the player’s family, as well as how much material and food falls into the pit. The end of the game, just like the end of Ugolino’s life, is inevitable death; however, if the player survives ninety days with all the family members alive, they get the “good” ending. This means that Ugolino learns to regret his life of betrayal, asks for forgiveness before his death, and wakes up at the base of mount Purgatory . There are as many other “bad” endings that vary on how many of the player’s family members survive at the end of ninety days, or if the player’s character dies early.

Jason Razaghi: “Numerical Interpretations in Purgatorio, Canto 33“

In a dialogue segment from Purgatorio, Canto 33, Beatrice mentions to Dante that there are obstacles to their retribution, “in which a five hundred ten and five, messenger of God, will slay the thieving woman and the giant that transgresses with her” (lines 43-45). When I was reading this specific dialogue, I had to pause for a moment because of how ambiguous the comment is. Her preface of the “stars already near” (Canto 33, line 41) was an indication that Beatrice is referencing a holy moment in time, whether it be in the past or the future. With the majority of Canto 33 being in a conversational setting, it is evident that Dante is attempting to include this nominal sequence with purpose and not just as a random sequence of numbers. The most challenging, yet exciting, problem I faced was the fact that this number has no definitive meaning inside the poem. The numeral sequence 515 must have been a number known to many at the time because of how influential and impending it was to their current times. For my final illustration, I chose to draw and paint a collage of important facets involved with the numeral 515, as well as try to decipher its meaning. The two 5’s symbolize the two different major events that Dante is referring to and the 1 recalls a vertical bridge going up to Heaven and towards God. In the background of the collage, I represented the Comedy by picturing Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso from left to right, much like how artists represent illustrations showing the passage on time, the passage of time being 515 years between the two holy references to the Roman empire. Moreover, I included the first version of the battle flag of the Holy Roman empire within the 1 digit to emphasize its accordance to papal and divine rule. The final touch of my illustration is the wreath around the entire numerical sequence, which is meant to represent Dante’s mind.

Daniella Sanidas: “Dante’s Tarot“

For my final project, I decided to create a series of three drawings that represent the events taking place in Inferno, Canto 5. The three drawings I made are based on three cards of the seventy-two archetypal images created by Pamela Colman Smith in 1909 under the direction of Arthur Edward Waite for the Raider Tarot Deck of Cards. The three cards I selected are “The Lovers” (which is the sixth trump or Major Arcana card in most traditional Tarot decks), “V of Cups,” and “The Devil” (which is the fifteenth trump or Major Arcana card in most traditional Tarot decks). I titled the first drawing: “The Sin” since it represents the scene in which Francesca and Paolo are reading the book and are seduced into lust, the sin that put them in the second circle of hell. “The Lovers” is a card that speaks about love, harmony, relationships, values, alignment, and choices, when it is upright. Yet, when it is seen in a reversed position, the card talks about disharmony, imbalance, and misalignment of values. Both positions of the card echo the events of the story of Paolo and Francesca: on the one hand, the deep feelings of true love that the two characters feel for each other; on the other, the treason that is committed when they submit to these feelings. The second drawing is titled “The Pity” and illustrates the scene in which Dante listens to the story told by Francesca in hell and feels so much pity that he faints. I selected the “V of Cups” card because it speaks about feelings of misery, loss, and grief. When this card is seen upright, it talks about sadness, loneliness and loss. However, when it is reversed, it refers to acceptance and healing. Because this card represents such negative feelings, specifically thinking that something is a certain way and then realizing that it is not, I connected it immediately with the pity that Dante experiences. The third and last illustration bears the title “Contrapasso” and visualizes Paolo abd Francesca’s destiny as an outcome of the sin they commit. For this illustration, I selected the card “The Devil,” which, when seen upright, represents attachment, addiction, restriction, and sexuality. When it is seen reversed, instead, it talks about exploring dark thoughts and detachment. Hence, I connected this representation of what happens when one gives into temptation to the miserable fate that like Paolo and Francesca experience.

Devin Shepard: “Simulating Dante’s Comedy in Virtual Reality“

For my final paper, I made an argument for how and why one might create a virtual reality simulation as an adaptation of Dante’s Divine Comedy. In the emerging technologically reshuffled paradigm that we are currently living, we find ourselves faced with an opportunity to revisit how stories of the past might be best reinterpreted in the present. Video games are different from most other media because there is inherently some level of open-endedness involved; Dante, as we know, goes on a journey defined by destiny, leaving little room for a player controlling a video-game avatar version of him to improvise while also being faithful to the original text. As Dante’s ancestor Cacciaguida tells him in Canto 17 of Paradiso, Dante was shown a specific set of famous people for the purpose of having examples in the poem he will ultimately write that will be recognizable and persuasive to the people who read it; giving a video game player too many options would upset the feeling of a divine plan that Dante so meticulously presents in his poem. In addition to options, games provide players with constraints that they must learn to work within as well. The issue of incorporating skill-based or problem-solving mechanics into games based on the Divine Comedy is that playing the role of Dante in a way that is faithful to the poem is not inherently challenging. Dante as a character is fairly receptive to the fact that he has suddenly found himself in the afterlife despite being still alive. And while he describes many incredible things, there is never a real sense of danger; his corporeal form is somehow not exposed to the environment in the same way that the souls that surround him are. There is also no sense that Dante might not progress; even in games where there is no violence or risk of losing based on a player character failing physically, there are plenty of games that are challenging in terms of puzzles, time limits, or learning curves. Even when Dante faints, he is quickly revived as far as the reader is concerned—they just read on, and there is no reason to believe they would not just play on, too, in a video game version. There is a sense that inhabiting the character of Dante is not challenging in the way that a video game demands because the story, obviously, moves forward. In this way, it might be best for our purposes to refer to the virtual reality experience not as a game, but rather as a simulation. The reason a simulation of Dante’s Divine Comedy would work, I would argue, is due to the fact that the environments and characters therein are eternally fixed, albeit interspersed with events and scenery that rewards extended contemplation, which I might add is a luxury not typical of most films unless you count pausing, rewinding, and fast forwarding as integral to the enjoyment of a film. There is a sense that Dante’s progression through hell, purgatory, and heaven also must be linear and unidirectional, but the eternal timescale is one that makes going backwards or forwards, even out of sequence, in a way that is easily accommodated by video game interfaces, might actually give a player more freedom even within a strict set of character and environment interactions.

Gabi Stack: “Elevating Dante“

The reason for creating a CD cover comes from the presence of music in Purgatorio. There are many direct references and allusions to music in this canticle. Specifically, at the very beginning of Canto 1 Dante writes that he “will sing of that second realm” (line 4) and later, after invoking the muses, he asks them to accompany his song (line 10), thus indicating that purgatory is to be regarded as music. I wished to keep my cover simple and focus on the two elements of Canto 1 that stood out to me the most: the eastern sapphire sky and the four stars. In the fifth stanza of the canto, Dante writes, “The sweet color of eastern sapphire, gathering in / the cloudless aspect of the air;” then, he continues: “I saw four stars never seen except by the / first people. // The sky seemed to rejoice in their flames” (lines 23-25). Those lines inspired me to design a deep blue background to represent the sky, cloudless as it is in the poem, and to add the four large burning stars. The title relates to Dante’s emerging from Hell and ‘elevating’ to the next level. Yet, its meaning can be applied in other ways to Purgatorio, in which Dante is elevating himself in preparation to meet God. He is moving up the mountain, so he is increasing in elevation quite literally, but he is also improving his mind and soul and becoming elevated in his understanding. Each of the songs have their own meanings related to different lines or concepts from Canto 1. The objective of my interpretation is to be a unique summary of the order of events in this canto, as well as a visually pleasing artwork representing the beauty of the sky described by Dante.

Jack Switzer: “Batman and Dante. The Tragedy of the Hero“

For my final project, I created a collage that combines the worlds of Batman and Dante, more specifically Batman’s world from the Long Halloween graphic novel and Dante’s Inferno. Dante and Batman are both tragic heroes in their stories and are connected through their suffering. On the one hand, Dante was exiled from Florence for fighting for what he believed in, a corrupt-free Catholic Church. On the other, Batman exiled himself, metaphorically, from the billionaire life of Bruce Wayne to become Batman and fight for what he believes in, justice for Gotham City. Dante begins his Commedia with the famous words, “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita” to describe his suffering as he is lost in life, physically and spiritually. Likewise, Batman is lost in his life through fighting a never-ending cycle of crime and violence in Gotham. Moreover, both Batman and Dante are driven by heavenly atonement to cope with their suffering. Dante can count on Beatrice, who sent Virgil to guide him through the circles of Hell. Batman has his murdered parents, Thomas and Martha Wayne, to serve as heavenly atonement. Batman also relies on his butler Alfred as a guide to achieve the “promise” that Batman made to his parents. Alfred is akin to Virgil in Dante’s Inferno, as a father figure and a mentor. More specifically, in the Long Halloween Batman attempts to solve a series of violent murders, which represent the constant suffering that Batman observes during his journey. Similarly, Dante is exposed to the suffering of the sinners. Batman and Dante are both anti-heroes in their own stories. Batman is not the perfect hero and often bends the rules to accomplish his goals; Dante does not act heroic in the Inferno and often lacks courage. However, both seek a heavenly atonement for the conclusion of their journey. For the collage, I decided to use construction paper and printouts of various characters from Dante’s Comedy and the Batman universe. For Batman, I selected his parents, his mentor Alfred, and his enemy Two-Face. For Dante, I selected his guide Virgil, Beatrice, and his teacher and mentor Brunetto Latini. I chose to use these characters because I believe they are all connected through their respective literary journeys. At the bottom of the collage, I crafted a fire to symbolize Hell/evil. Although the deepest part of Hell is cold, fire is a better connotative association for Hell. The design is supposed to lead viewers from the fire depicted at the bottom of the collage through the purple at the middle and then to heaven, which is represented by a semi-circle of white construction paper. In Paradiso, Dante journeys through the various rings of heaven. However, I did not include a full circle because I did not want to insert all of heaven in the collage. By restricting to a half circle, I aim to argue that heaven cannot be fully displayed or interpreted.

Isidoro Villa Ligero: “Alexander the Great’s Flight and Libro de Alexandre in Dante’s Inferno“

The correlation between the flight of Alexander the Great as described in Libro de Alexandre and Ulysses’ flight in Inferno, Canto 26 is worth exploring in relationship to the events featuring in Cantos 24, 25, and 26 in Inferno. Even though in Canto 26 there is no mention of Alexander, it would be beneficial to interpret his figure as a constant and present motif shaping the protagonist of the canto, Ulysses. Questions on why Dante decides not to mention Alexander and chooses Ulysses to describe what he saw on his flight and why the flight that Ulysses describes in Canto 26 is similar to the flight featuring Alexander in Libro de Alexandre, are legitimate. For my final paper, I explored how the Libro de Alexandre and the Comedy are related and offer an hypothesis on why Dante choose the character of Ulysses instead of Alexander to explain the concept of searching for knowledge without the purpose and intention of being close to God. I propose that the Comedy works like a medieval exempla if we consider the poem as a group, that is, its three parts: Inferno, Purgatory, and Paradise. The teacher of the poem is undoubtedly Virgil, who represses Dante’s curiosity since the early stages of Inferno. More than curiosity, scholars identifies the term with pietas, or else compassion. The Comedy is related somehow to the wisdom literature of the Middle Ages, although it does not seem integrated into this genre in its entirety. Many of Dante’s questions remain unanswered or are answered by souls without the intervention of his teacher. Dante’s plans for his Comedy was clearly not to be part of wisdom literature. Ulysses’ voyage is indeed a search for knowledge further away than the limits imposed by God. For that voyage, Ulysses used wings: “of our oars we made wings for the mad flight, always gaining on the left side” (Canto 26, lines 124-126). Likewise, Alexander challenges God after starving for three days and builds some wings in order to fly. During his flight, he is able to understand the secrets of antiquity, as well as see the Earth as never before. Alexander measures Africa and sees Syria, Asia, Africa, and Europe. The map of the world takes the form of a T, from Isidorus´s Etymologiae, and represents a reflection of the shape of the human body: Asia is the torso, Africa is the left leg, and Europe is the right leg. In Canto 26, Ulysses tells Dante that all he desires is to gain “experience of the world and of human vices and worth” (lines 97-99), but cannot see the world beyond the limits marked by Hercules.

Abby Williams: “From the Dark Woods to the Stars”

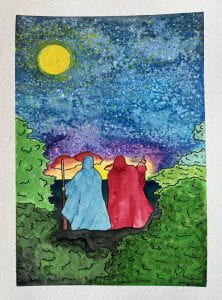

For my final project, I painted a scene inspired by the first lines on Inferno, Canto 1, and the last lines of Inferno, Canto 34. Specifically, I referred to the first three lines of Canto 1: “When I had journeyed half of our life’s way, I found myself within a shadowed forest, for I had lost the path that does not stray.” I also drew on the last lines (133-139) of the final canto in Inferno: “My guide and I came on that hidden road to make our way back into the bright world; and with no care for any rest, we climbed—he first, I following—until I saw, through a round opening, some of those things of beauty Heaven bears. It was from there that we emerged, to see—once more—the stars.” My watercolor painting depicts Dante and Virgil in the middle of the page. Dante is represented wearing his traditional red cloak with the hood raised. He is pointing at the stars in the sky in order to convey his wonder and excitement at seeing the stars once again. I represented Virgil in blue, as many other paintings also do, and holding a staff, signifying his role as guide and protector of Dante. This element plays upon Dante’s many Biblical references, as well as depictions of God as a shepherd. Virgil, too, has the role of shepherding Dante through Hell and preparing him for paradise. Virgil and Dante have their backs to the dark wood, representing their leaving behind of the darkest part of their journey, which began in a dark forest filled with fear and confusion. In this case, the dark wood represents both the physical dark wood encountered in the first canto, as well as a metaphorical representation of the entirety of Hell. Covering the top two thirds of the page is an expansive sky filled with stars and the moon. On the horizon, the sun is rising, and three clouds are lit up by its rays. The rising sun is inspired by Purgatorio, Canto 1: “Daybreak was vanquishing the dark’s last hour, which fled before it; in the distance, I could recognize the trembling of the sea” (lines 115-117). I put the sunrise directly between Virgil and Dante for symmetry but also to make it a focal point in the painting. The sun represents rebirth, a new day, warmth, and renewed hope for the future, now that the worst part of their journey is behind the two characters. There is a slight blue tinge to the area near the rising sun, signifying the ocean that surrounds the island of Purgatory and that the sun lights up.

Jane Wineland: “From the ‘Empyrean’ to the ‘Omega Point.’ Dante’s Comedy and the Evolutionary Theology of Teilhard de Chardin“

Unfortunately, many readers of the Divine Comedy go no further than Inferno, never experiencing Purgatorio and Paradiso. While it is true that these last two canticles are far less visual, focusing heavily on theology and philosophy, they bring to the commedia an important motif not found in Inferno. It is convergence, meant to describe human souls gathered together, in the eternal light of God, after death. If convergence is understood in this light, then its opposite is souls eternally isolated, cut off from God and from one another. It is the love, unity, communication and joyful interchange among the blessed dead, which draws them ever upward, binds them ever closer to one another and to God, and pulls them further and further into His light. For my final paper, I traced the journey of Dante the pilgrim, pausing on relevant passages leading up to the convergence he eventually experiences in the “Empyrean.” I also compared the “Empyrean” with the “Omega Point,” a sweeping theory of the of the universe developed by the French Jesuit priest, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Convergence in Purgatory – the gradual upward movement wherein souls become unified ever more closely – involves the transformative powers of light, contrition, purification, and the healing power of God. These overlapping and intersecting motifs are immediately visible in the very first pages of Purgatorio. Having escaped with Virgil “the deep night that / makes the valley of Hell forever black,” (Canto 1, lines 44-45), Dante finds himself on the outermost edge of the realm where he will be confronted inescapably with some dangerous truths about himself. In Virgil’s words to Cato, we recall how close Dante was to damnation: “This man never saw his last evening; but / through his folly he was so near it that not much / time remained to turn” (Canto 1, lines 58-60). If impossibility exists in degrees, we have a lovely example of it in the final cantos of the commedia, as “what-is-impossible-to-describe” becomes yet more impossible, and more impossible, and still more impossible. We partake in a vision of God that is so exalted and awe-inspiring that it stands unparalleled in all of literature. Every trace of Dante’s mortality has been effaced; his spiritual sight is now so acute he is drawn “deeper and deeper into the ray of the supreme Light that / is true in itself.” (Canto 33, lines 52-54). Drawn into the very depths of God, Dante is astounded to see at its very center the effigy of all humanity that Christ died to save. All things have met and converged in God.